Few novels have had the impact of Ulysses. As humanity is endlessly curious about itself, the books that survive tend to be those that reflect some profound human experience. Ulysses is one such book. Its central theme is the everyday life of men and women which Joyce has wrought with such skill that it resonates as enduring art. Through the inner lives of its characters, Ulysses offers a detailed portrait of a city and the people who move through it. Like Homer’s Odyssey, Dante’s Divine Comedy, or Cervantes’ Don Quixote, Ulysses stands as a monument to how literature can embody the human spirit.

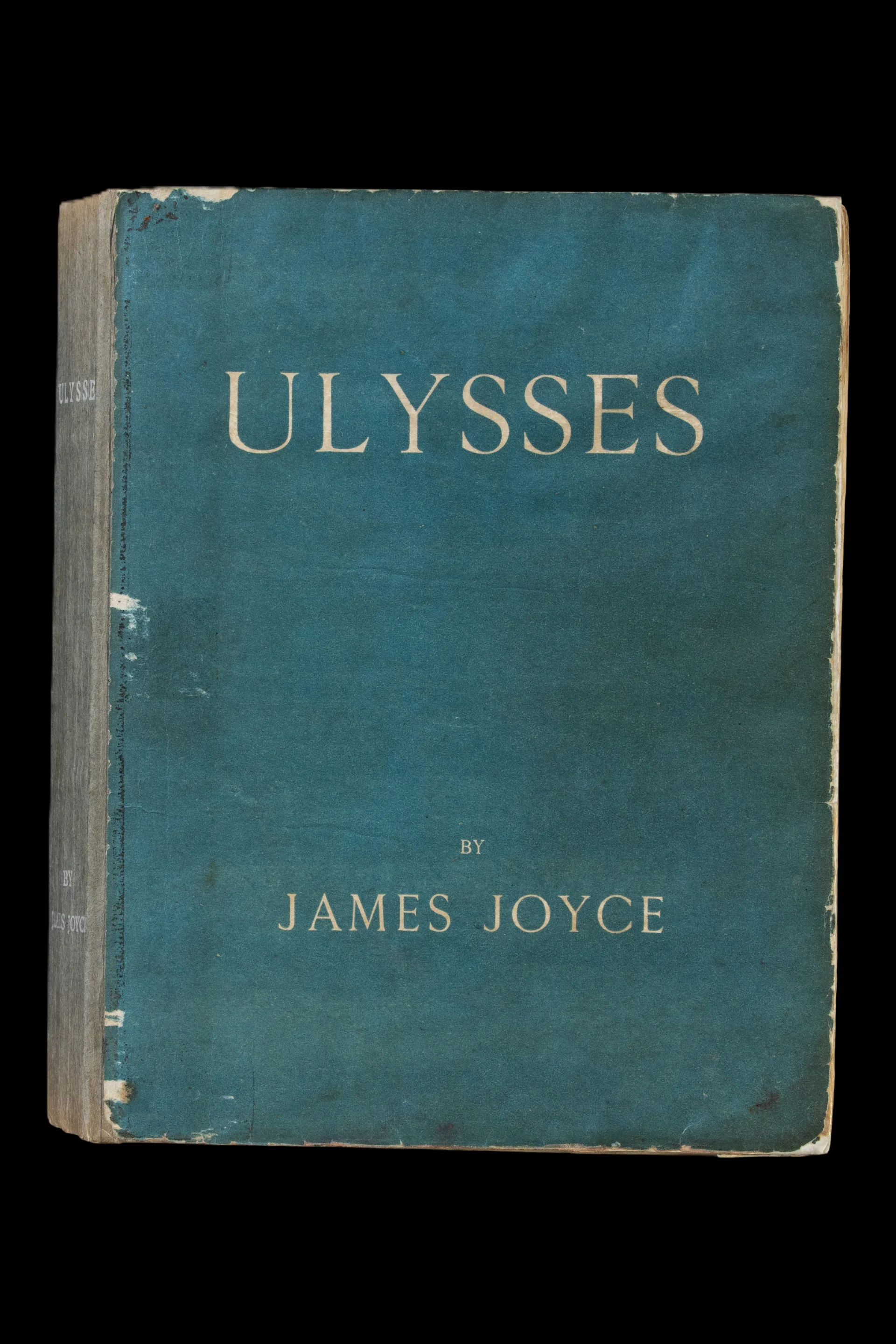

Ulysses was first published in Paris by Sylvia Beach of Shakespeare and Company in 1922. Before publication, the book was partly serialised in the American journal The Little Review from 1918 to 1921. The magazine soon had to cease publishing the extracts after a New York court ruled the writing to be obscene. Joyce feared his book would never be published. In the end, the type for the book was set by hand in Dijon by French printers who could not read English. Ulysses was banned in the United States and the United Kingdom for over a decade. In Ireland, it was never officially banned, but copies failed to make it through customs. For many years the only place you could buy Ulysses in Ireland was at the James Joyce Tower.

At its core, Ulysses recounts a single day—16 June, 1904—in Dublin, following the movements of Leopold Bloom and Stephen Dedalus. On the surface, the plot appears prosaic: Bloom cooks breakfast, goes to the chemist, attends a funeral, eats lunch, visits a pub, meets Stephen and eventually returns home. But what makes Ulysses remarkable is its experimentation with form. Joyce employs a range of narrative techniques most notably stream of consciousness, parody and free indirect discourse. Ultimately Ulysses is epic in form. The great mass of detail is so encyclopedic that it has been said that, in the end, we know more about Mr Bloom than we do about any other character in world literature.